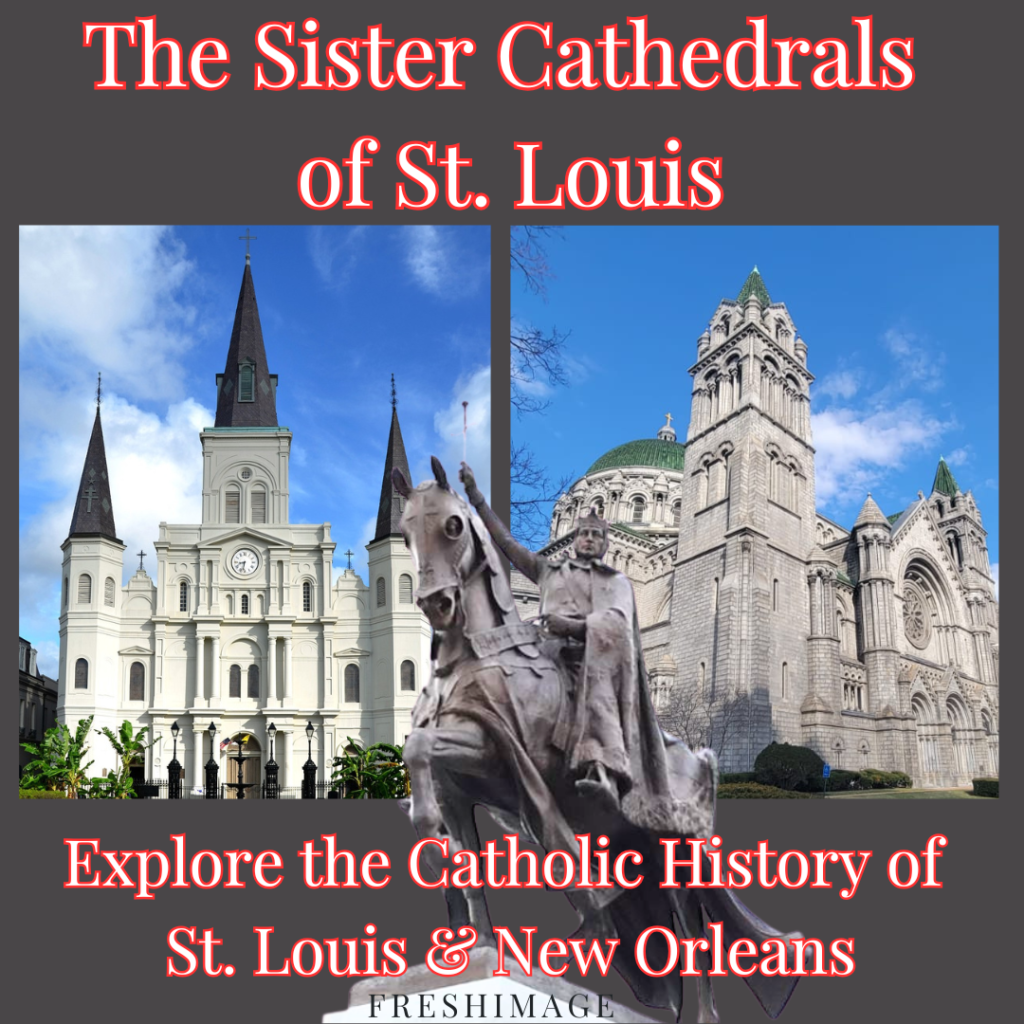

San Louisians are justifiably proud of our beautiful and cherished landmark, the Basilica of St. Louis. Besides being a place of worship, the seat of the Archdiocese, and the most important center of spiritual life for St. Louis Catholics, the Basilica also stands as a testament to the historical, cultural, and architectural legacy of the city. A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to visit her “elder sister” – another basilica under the patronage of St. Louis, the Cathedral of New Orleans, the oldest cathedral in the United States. The choice of the same patron, Louis IX, the King of France, reveals the common history shared by both cities, in which France played an important role. The French influence in the creation and development of the St. Louis area, reflected in the names of many city streets and historical sites, is well-known. However, the full account of the history of our region presents a complex picture, with many aspects not commonly known. How many people realize that the city of St. Louis was, for several decades, a part of the Spanish Empire? But let’s start from the beginning.

In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle, a French fur trader, declared that the vast land along the Mississippi River belonged to France. That claim, however, was hotly contested by Britain. La Salle called the new territory Louisiana in honor of the French King Louis XIV. Upper Louisiana included the St. Louis area, while Lower Louisiana encompassed New Orleans. French rule, however, did not turn out to be permanent.

As a consequence of the Seven Years’ War among the European powers and their colonies, Louisiana became a part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain in 1762, and the British gained control over the territories east of the Mississippi River. The new status did not last long. After a series of political and military setbacks, Spain decided that Louisiana was too expensive to maintain and created some security problems, and ceded control of the territory back to France (Third Treaty of San Ildefonso, 1800). France, in turn, much to the surprise of American delegates in Paris, James Monroe and Robert R. Livingston, accepted an offer from the United States to purchase the colony. In 1812, Louisiana was split into the Territory of New Orleans and the Territory of Missouri. The Territory of Missouri formally became a new state of the Union in 1821.

The construction of the original church on the site of the Cathedral of New Orleans began in 1724 under the supervision of Adrien de Pauger, who arrived from France in 1721. The church was consecrated shortly before Christmas of 1727. Hardly a decade passed without a major repair or renovation of the church, as it was subjected to several calamities including hurricanes, tornados, lightning, fires, termites, and soil subsidence. The most important renovation project started in 1849 under the supervision of architect J.N.B. de Pouilly. Much of the present interior dates to 1851-1852.

The iconic facade of the cathedral, with its three towers, windows, and main entrance surrounded by statues of St. Louis and St. Joan of Arc, together with the adjacent historical Jackson Square, are at the heart of the oldest part of New Orleans – the French Quarter. The secluded St. Anthony’s Garden, located behind the cathedral, features a statue of Jesus raising his arms towards heaven, casting a powerful shadow against the church building at night. The high altar, built in 1852 in Belgium, consists of a white marble table supported by figures of four angels. On each side of the tabernacle are statues of St. Peter with the keys and St. Paul with the Bible. Above the main altar is a large painting of St. Louis by Erasme Humbrecht. The vaulted ceiling depicts the Lamb of God, scenes from the life of Christ, the four evangelists, and the apostles. Six Corinthian columns support an entablature and pediment crowned with three female figures representing Faith, Hope, and Charity. Beneath the sanctuary, eleven bishops and archbishops are buried.

The Saint Louis Cathedral of New Orleans has been the site of several historical events. Among these, one must mention Andrew Jackson’s return to New Orleans in 1840 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of his victorious battle against the prevailing British forces attempting to take the city. He came by steamboat, disembarked at the riverfront, and walked across the square to the cathedral at attend a commemorative Mass. Much later, Zachary Taylor enjoyed the same triumphant welcome of over 40,000 people on Jackson Square and neighboring streets when he arrived (also by steamboat) to a one-hundred-gun salute. Similarly to Jackson, Taylor, immediately upon his arrival, went straight to the cathedral for a solemn Mass.

Andrzej Zahorski is Director of Music at St. Anselm Parish in St. Louis, MO. He holds a doctorate of musical arts from Stanford University.