By Tony Crescio

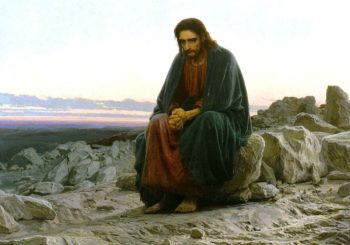

When asked if the Gospel was a source of consolation for him, Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini, replied that when it came to the Gospel of Jesus Christ he ‘completely rejected the idea of consolation,’ adding that he saw the go...

Read More

Read More