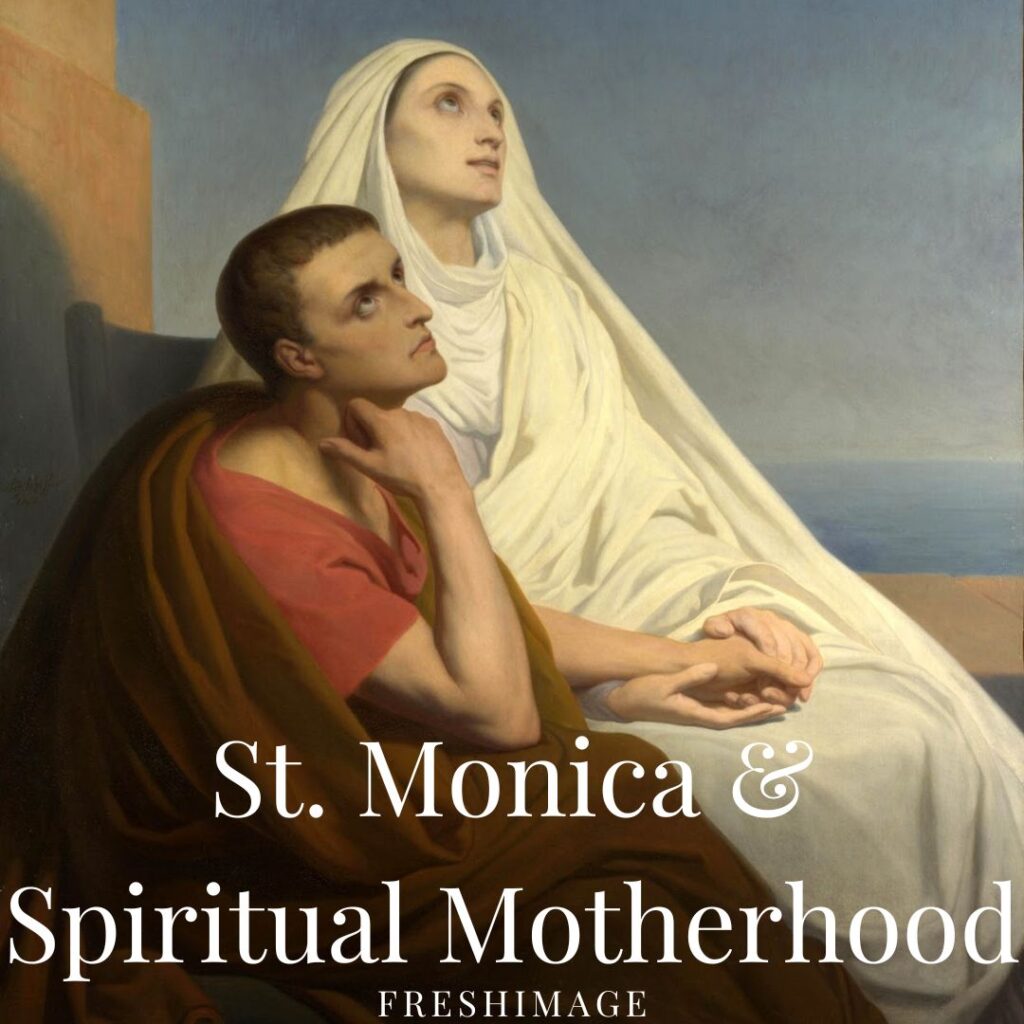

Among other things, the celebration of the life of St. Monica today represents the fulfilment of a son’s prayer. At the end of Book Nine of his Confessions, St. Augustine of Hippo asks his readers to pray for his parents, most especially within the Eucharistic liturgy.

Inspire others, my Lord, my God, inspire your servants who are my brethren, your children who are my masters, whom I now serve with heart and voice and pen, that as many of them as read this may remember Monica, your servant, at your altar, along with Patricius, sometime her husband. From their flesh you brought me into this life, though how I do not know. Let them remember with loving devotion these two who were my parents in this transitory light, but also were my brethren under you, our Father, within our mother the Catholic Church, and my fellow-citizens in the eternal Jerusalem…So may the last request she made of me be granted to her more abundantly by the prayers of many, evoked by my confessions, than by my prayers alone (Confessions, 9.13.37).

Though this paragraph may seem a simple bit of filial piety and even perhaps sentimentality, in actuality it contains almost everything Augustine would want us to remember about his mother, Monica. The two had a wonderfully complicated relationship. On his own telling, there was no other human person who had as big of an influence on the great bishop of Hippo and the Church’s Doctor of Grace.

By all accounts, Monica was a remarkable woman in many ways. Before Augustine came to realize this for himself, he was often reminded by future fellow Father of the Church and bishop, Ambrose of Milan, of how lucky Augustine was to have such a mother as Monica. Augustine writes that Ambrose held her in high esteem “for her deeply religious way of life. Her spiritual fervor prompted her to assiduous good works and brought her constantly to church; and accordingly when Ambrose saw me he would often burst out in praise of her, telling me how lucky I was to have such a mother” (Confessions, 6.2.2). For years, the one-day Doctor of Grace failed to recognize in his mother, Monica, the precious gift of God’s grace she was. Instead, Augustine saw Monica as clingy and even as a bit of a nag.

The best evidence of this comes in Book Five of the Confessions. Here we join an Augustine who is frustrated with his state in life. At this time a professional rhetor and teacher of rhetoric in his native North Africa, Augustine found himself teaching low-caliber students and without the fame and fortune he so desperately desired (see Confessions, 5.8.14). Consequently, Augustine decided to turn his sail towards the capital of the empire, Rome. For her part, Monica was determined to accompany her son. However, for Augustine, this was less than ideal. He tells us that Monica was always by his side, and it seems quite indefatigable in her efforts to persuade her son to return to the faith of his youth. Accordingly, Augustine made plans to ditch Monica at port and sail to Rome unencumbered by her presence. In the same book he writes, “She held on to me with all her strength, attempting either to take me back home with her or to come with me, but I deceived her, pretending that I did not want to take leave of a friend until a favorable wind should arise and enable him to sail” (Confessions, 5.8.15).

The Bishop of Hippo is masterful in his nuanced recounting of this episode. As he is famously known for, Augustine believed that God would not allow evil to exist could he not bring good from it (see Enchiridion, 11, cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 311). And this included the sinful action of human creatures. Looking back, then, Augustine could see how God’s loving providence used Augustine’s deception as a means for bringing both himself and his mother one step closer to Himself. Augustine puts it this way:

You took no heed, for you were snatching me away, using my lusts to put an end to them and chastising her too-carnal desire with the scourge of sorrow. Like all mothers, though far more than most, she loved to have me with her, and she did not know how much joy you were to create for her through my absence” (Confessions, 5.8.15).

While the immature Augustine incorrectly saw his mother as a persistent nag, the mature Augustine could see that at this time in his life, Monica was yet deficient in faith, and consequently impatient. God, therefore, was teaching Monica to trust Him more, patiently inviting her to realize that her love for Augustine was not nearly so untiring as the One Who would remember even those whose mothers had forgotten them (see Isaiah 49:15).

Though difficult, the lesson God was teaching Monica at this time was far more straightforward than the curriculum He had prepared for the future Doctor of Grace. And the way Augustine describes the Divine Teacher instructing him tells us much about how all-encompassing yet subtle the Bishop of Hippo came to understand the operation of Divine Providence to be. Such is suggested by the passage just cited where Augustine writes, “you were snatching me away, using my lusts to put an end to them.” You see, it wouldn’t take long before God had Augustine surrounded. For although Augustine outran his mother for a time, he was running right towards another instrument of Divine Providence in his life across the Mediterranean, St. Ambrose of Milan (see Confessions, 6.1.1-6.3.3). Together with others, the two would serve as God’s instruments for bringing about Augustine’s conversion.

In time, Augustine would come to realize how God’s all-encompassing love had been designed to draw this prodigal back to Himself. And when he did, he also realized just how priceless his mother, Monica, had been to the Divine scheme. He thus describes his deception from the vantage of history this way,

I lied to my mother, my incomparable mother! But I went free, because in your mercy you forgave me. Full of detestable filth as I was, you kept me safe from the waters of the sea to bring me to the water of your grace; once I was washed in that, the rivers of tears that flowed from my mother’s eyes would be dried up, those tears with which day by day she bedewed the ground wherever she prayed to you for me (Confessions, 5.8.15).

Incomparable. A professional rhetor by training who left us more than five million words whereby to contemplate the most beautiful and sublime phenomena this side of eternity and hereafter, Augustine chooses not to describe his mother with any positive adjective, but rather in essence refuses to describe her. Why?

Again, this is no empty show of filial piety. The reason that from Augustine’s perspective there is no complete way to describe Monica’s role in his life is because in and through her Augustine encountered the very presence of Divine Love, which no words can adequately describe. But, being who he is, Augustine does try to describe the phenomenon of Love he knew in Monica. Further on in The Confessions, Augustine writes of Monica, “But I will not pass over anything that my soul brings forth concerning that servant of yours who brought me forth from her flesh to birth in this temporal light, and from her heart to birth in light eternal” (Confessions, 9.8.17). Monica brought Augustine to birth physically, but more importantly, by cooperating with God’s grace helped give birth to Augustine spiritually. Monica was, if you will, Augustine’s spiritual mother.

By describing his mother this way Augustine is really saying that Monica lived with the loving intentionality a member of the Body of Christ, the Church, ought to. For Monica lived with the aim of bringing her son to new and everlasting life in Christ. Augustine describes this as the role of all the faithful in his work Holy Virginity, where he compares the life of the Church to the life of Mary, the Mother of God, writing, “On the other hand, the Church as a whole, in the saints destined to possess God’s kingdom, is Christ’s mother spiritually” (Holy Virginity, 6.6). For Augustine, regardless of one’s state in life, to bring others to birth in Christ is part and parcel of one’s Christian vocation. Thus, later in his life in his extended debates with the Pelagians surrounding the goodness of marriage, sexuality, and the necessity of infant baptism, Augustine writes, “This, after all, is and ought to be the intention of Christian married couples: that children who are born may be prepared for rebirth” (Against Julian, 4.1.3).

From his earliest recollection, though not without complication, this is how Augustine remembered his relationship with Monica. As a young Christian woman married to a then indifferent non-Christian, Monica found herself bearing the weight of bringing her children to birth in Christ alone. Consequently, Augustine writes that in his youth, “my mother did all she could to see that you, my God, should be more truly my father than he was…” (Confessions, 1.11.17). How did Monica do this? Most simply, by speaking to her children about Christ and making the practices and signs of the faith part of their lives. In Book One of The Confessions, Augustine writes,

While still a boy I had heard about the eternal life promised to us through the humility of our Lord and God, who stooped even to our pride; and I was regularly signed with the cross and given his salt even from the womb of my mother, who firmly trusted in you (Confessions, 1.11.17).

Even though Augustine tells us that his father, Patricius, who himself was to convert to the faith later in life did not interfere with Monica’s efforts, that Monica sought to form her children in the Christian faith alone was no small task. It was therefore undoubtedly clear to Augustine that what enabled his mother to do this was her own vigorous practice of the faith. By looking at what Augustine highlights about the life of Monica, then, gives us insight into how we too might live our Christian vocation as spiritual mothers and fathers so that we might bring those around us, especially our children, to birth in Christ day by day.

Here, there are really no surprises. Augustine’s discussion of Monica’s life makes clear that what enables one to live as a spiritual mother or father is at bottom striving to live the Christian life in its entirety, regardless of circumstance or how hopeless the situation we face may look from time to time. That said, we can draw some specific elements from Augustine’s choices of what he tells us of his mother’s life.

The first, and perhaps most important, lesson to draw from Augustine’s portrayal of Monica when it comes to the life of spiritual motherhood or fatherhood, is the importance of living with the clear realization that we are all, without exception, works-in-progress. Augustine is not shy from letting us know that, for all her holiness, his mother was a broken human being. This is seen in two separate instances in his Confessions. One has already been mentioned in detailing Augustine’s famous deception of Monica. There we saw that Augustine wrote that in allowing this to happen, God was “chastising [Monica’s] too-carnal desire with the scourge of sorrow” (Confessions, 5.8.15). What Augustine is saying is that his mother still had an unhealthy this-worldly attachment to him. In other words, Monica was too focused on being physically near to Augustine and keeping him under her watch than having faith in God to work Augustine’s conversion through the very many means Augustine details throughout The Confessions. The second instance appears in Book Nine, where Augustine provides a more extended discussion of Monica’s life, beginning with an unhealthy and “furtive fondness for wine” in her youth (Confessions, 9.8.18). At that time, a maid of the family acted as God’s instrument of Providence in Monica’s life, calling attention to her developing vice in order to heal her from it (Confessions, 9.8.18).

In addition to highlighting the fact that all of us, even those among us one day destined to be elevated to Christ’s Altar, are works-in-progress, these episodes from Monica’s life also serve to highlight three virtues at the core of her character that enabled her to become a spiritual mother to her son. These are the virtues of fortitude, patience, and perseverance. Throughout The Confessions, we find Monica facing obstacles of various kinds in her life. We have already mentioned some here, trying to raise children in the Christian faith single-handedly and overcoming personal vices. And we can add that for she was also charitably patient with a difficult mother-in-law and her sometimes-unpleasant husband, Patricius (Confessions, 9.9.19-20. In each instance, Monica perseveres, courageously striving to live in accordance with the Truth of the Christian faith, whether that meant conforming herself to it or seeking to draw others to it. Two unique instances of this might be mentioned.

The first comes just after Augustine deceives her and sets sail for Rome under the cover of night. Untiring in her love for her son, Monica sets sail after him. Here, for all her imperfections, the courage of Monica’s faith in God shines through. Evidently, the ship encountered some difficulty on the seas amid the voyage. Despite the danger, Monica remained undaunted.

Indeed, amid the perils of the voyage it was she who kept up the spirits of the sailors, though in the ordinary way it is to them that inexperienced and frightened travelers look for reassurance. She, however, had dared to promise them that they would come safely to port, because you had yourself made this promise to her in a dream (Confessions, 6.1.1).

Another instance is seen in the advice Monica gave to other wives who, like her, struggled with unfaithful and what Augustine calls “hot-tempered” husbands. Evidently, Patricius’ bad temper was known. Augustine tells us that “these other wives knew what a violent husband [Monica] had to put up with, and were amazed that there had never been any rumor of Patricius striking his wife, nor the least evidence of its happening, nor even a day’s domestic strife between the two of them…” (Confessions, 9.9.19). What was Monica’s secret? Not blind obedience to her husband. Rather, Augustine tells us, it was Monica’s patient love that won the day. For, instead of confronting him when angry and provoking him to further anger, Monica’s virtue bore the weight of her husband’s vice. She would wait for his anger to subside, and then talked things through calmly with him (Confessions, 9.9.19). Augustine adds that “those who followed [Monica’s advice] found out its worth and were happy; those who did not continued to be bullied and battered” (Confessions, 9.9.19).

The next logical question, then, is how did Monica come about such extraordinary virtues? By living a Eucharistic life. Augustine’s account of Monica’s daily life makes clear that she was a woman of the Eucharist in every sense. Augustine tells us that Monica attended Mass daily, “never a day would pass but she was careful to make her offering at your altar” (Confessions, 5.9.17). For Monica attending Mass was not a simple act of habit, but a true participation in the sacrifice of Christ that formed the core of her existence. Accordingly, what Augustine describes as taking place in the souls of those who so participate in the Eucharist in Book Ten of the City of God took place in Monica. She was filled with the virtues of Christ, or said differently, the Virtue that Is Christ. Consequently, Monica was not one who simply received the Eucharist and went on her way, but Monica’s whole life became Eucharist, a life of self-sacrificing love for all around her. We have already seen this in her loving patience with her mother-in-law, husband, and son, in her encouragement of the sailors and counseling of other wives who dealt with difficult husbands. But Augustine also tells us that Monica’s “spiritual fervor prompted her to assiduous good works,” including serving the poor and needy (Confessions, 6.2.2). It was her daily participation in and living out the Eucharist that made Monica such a powerful exemplar for those around her. For by living in accordance with Christ’s presence in her, Monica magnified that presence and served as a channel of God’s grace to all those around her, drawing them to Him little by little.

Finally, regular participation in the Eucharistic liturgy and reception of the Eucharist also formed in Monica a prayerful heart. In addition to her daily attendance of Mass, Augustine writes, “twice a day, at morning and evening, she was unfailingly present in your church, not for gossip or old wives’ tales but so that she might hearken to your words, as you to her prayers” (Confessions, 5.9.17). To her participation in the communal prayer of the Church, Monica added an intense life of private prayer. Throughout the Confessions, Augustine highlights the tearful prayers of Monica for the conversion of her prodigal son. For example, in Book Three of the Confessions, Augustine writes, “you heard her, O Lord, you heard her and did not scorn those tears of hers which gushed forth and watered the ground beneath her eyes wherever she prayed” (Confessions, 3.11.19). It is with reference to these tearful prayers that Monica famously received this consolation from a bishop whose advice she sought regarding her son, “A little vexed, he answered, ‘Go away now; but hold on to this: it is inconceivable that he should perish, a son of tears like yours’” (Confessions, 3.12.21). The famous words of this bishop might prompt us to ask, what exactly was so special about Monica’s tears?

Monica’s tears were not a simple expression of sentimentality. Augustine’s account makes clear that Monica’s tears indicated the Eucharistic nature of her prayers. Said differently, Monica’s tearful prayers were an expression of the agony of her spiritual motherhood, the pangs of giving birth to Christ in her son in participatory imitation of Christ Who once painfully gave life to the Church through His Sacrifice on the Cross. This becomes evident in the language Augustine uses in reference to his mother’s tearful prayers on his behalf in two occasions in Book Five of the Confessions. In the first, using explicitly Eucharistic language, Augustine writes,

Through my mother’s tears the sacrifice of her heart’s blood was being offered to you day after day, night after night, for my welfare; and you dealt with me in wondrous ways. You, my God, you it was who dealt so with me; for our steps are directed by the Lord, and our way is of his choosing. What other provision is there for our salvation, but your hand that remakes what you have made? (Confessions, 5.7.13).

Monica’s tears ran with the Blood of the Lamb, and thereby ran down her wayward son. The second instance is more subtle, yet I think, more eloquent. It appears shortly after the passage just quoted, and just after Augustine deceives Monica and sets sail for Rome. Augustine writes,

Full of detestable filth as I was, you kept me safe from the waters of the sea to bring me to the water of your grace; once I was washed in that, the rivers of tears that flowed from my mother’s eyes would be dried up, those tears with which day by day she bedewed the ground wherever she prayer to you for me (Confessions, 5.8.15).

Augustine here is clearly drawing a connection between his mother’s tears and the sacred waters of baptism. It is as though, in retrospect, Augustine sees that until he was saved through the waters of the sacrament of baptism, Augustine was kept safe by the water of his mother’s tears. More to it, in this imagery, Augustine suggests that the tears which flowed forth from his mother’s eyes served as the river by which Divine Providence carried him safely to the baptismal font. For tears saturated with the Blood of the Lamb could only flow in this direction.

It is not much of a leap to assume that Monica’s eyes shed similar tears for her husband, Patricius. In the end, God’s grace saw fit to allow Monica to see the conversion of both her husband and her son before she concluded her earthly pilgrimage. Put differently, Monica was given the grace to give spiritual birth to her husband and her son alike. And we have seen how she did this, through a Eucharistic life characterized by the virtues of fortitude, patience, and perseverance and undergirded by prayer. Taken as a whole, in Monica, we see a participatory imitation of the Love of God which made that Love present to those around her, and drew those around her to that same Love. With the Hound of Heaven, Monica tirelessly tracked down her prodigal son, and the fruit of her spiritual labor is on full display each year on the 27th and the 28th of August. On the 27th we remember this incomparable spiritual mother. And, tomorrow on the 28th, the Church celebrates the life of her biological and, more importantly, spiritual son, St. Augustine of Hippo, known today as a saint, Doctor, and Father of the Church. There are very few who have influenced the life of the Church and contributed to her welfare than St. Augustine. But who was Augustine apart from the sacrifice of his mother’s tears?

Before Augustine wrote what are his most famous words, they were exemplified to him by his mother, Monica. In the opening paragraph of the Confessions, Augustine writes, “You [God], stir us so that praising you may bring us joy, because you have made us and drawn us to yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you” (Confessions, 1.1.1). No one save Monica taught Augustine that he was made for no one except for God through her relentless love for him. Monica lived out of the sure conviction that her son was made for nothing less than the loving embrace of our Heavenly Father, was made to be a saint. Today let us celebrate the life of St. Monica by imitating her loving conviction that those entrusted to our care are made for the very same, and commit ourselves to living accordingly so as to give spiritual birth to them in Divine Love.

Your servant in Christ,

Tony

Tony Crescio is the founder of FRESHImage Ministries. He holds an MTS from the University of Notre Dame and is currently a PhD candidate in Christian Theology at Saint Louis University. His research focuses on the intersection between moral and sacramental theology. His dissertation is entitled, Presencing the Divine: Augustine, the Eucharist and the Ethics of Exemplarity.

Tony’s academic publications can be found here.