The truest solitude is not something outside you, not an absence of men or of sound around you; it is an abyss opening up in the center of your own soul. (New Seeds, 80)

In Ch. 11 of New Seeds of Contemplation, Thomas Merton offers a rich reflection on the fruitfulness of solitude and the tools for learning to be alone. When we reflect on solitude, we may first imagine a lonely path through the woods, a rustic cabin resting on a hilltop, or a lonely bench resting in the shade of trees. However, this is only part of the story. Solitude has as much to do with the interior as well as the exterior. Solitude is where the Lord truly speaks to our hearts. We recall some great moment in scripture, which occurred in silence; Samuel hearing the voice of God in the silence of the night, the Prophet Elijah hearing the Lord in a small whispering voice. At the Annunciation, Our Blessed Mother was visited by the angel Gabriel in the silence of the night. At the Nativity, Jesus came into the world in an obscure cave in the still of the night. At the Crucifixion, although a horrific spectacle, at a certain point, Jesus says very little and our Blessed Mother and the disciple Jesus loved stand at the foot of the Cross; weeping.

Over the past several months we’ve found ourselves having to spend a lot of time alone. Alone with the members of our proverbial bubble but never-the-less alone. The pandemic has put us in isolation from family and friends. Physical isolation or separation from others is a purely physical reality. When we speak of solitude; we’re not speaking of an imposed solitude but rather a spiritual alone-ness with God. We’re alone with Him for a purpose. Solitude, unlike isolation is meant to be a source of life, truly a way to seek Him.

But when you pray, go to your inner room, close the door, and pray to your Father in secret. And your Father who sees in secret will repay you (Mt. 6:6).

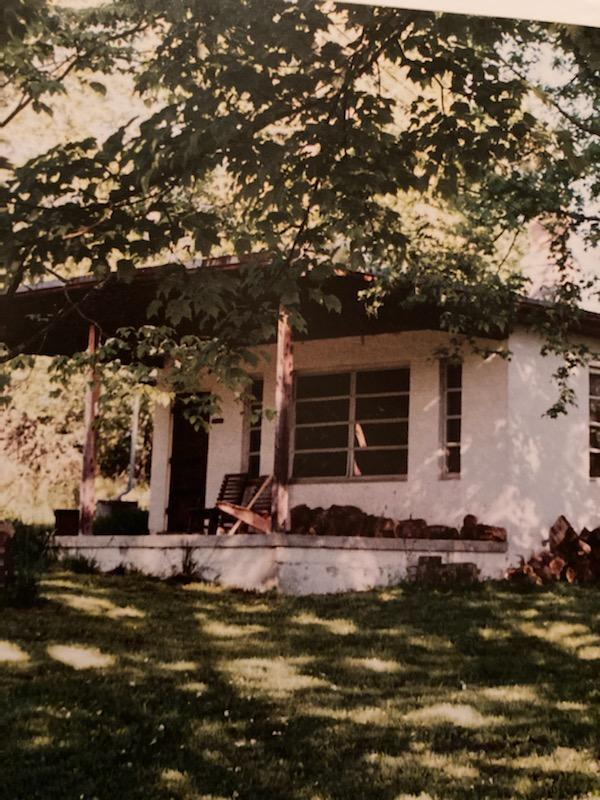

Father Louis (Thomas Merton) entered the monastic life in December of 1941. After twenty-four years of living his monastic life in community, he was given permission to live the eremitical life- that is the life of a hermit. In 1965 Merton’s Abbot gave him permission to build and live in a small house situated near the monastery. Merton prayed, ate, and slept in the hermitage for the remaining three years of his monastic life. He was no longer obligated to attend the liturgy and community exercises with his brother monks. He prayed alone in solitude. This arrangement is ascribed for in chapter one of the Rule of Saint Benedict.

Second, there are the anchorites or hermits, who have come through the test of living in a monastery for a long time, and have passed beyond the first fervor of monastic life (Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter One).

The monk after living several years in community with the support of his brothers may be prepared to go into the dessert and to do true battle for Christ the King; in order to continue the struggle to achieve purity of heart. In this battle with Christ the monk continues to grow in virtue and grace. He is ready to go out on his own, as it were, without the physical support of his brothers. However, he is still attached to his monastic brethren in a deeper spiritual reality. He continues to be attached to the Church; by the sacramental bond of Baptism and monastic vows. The monk supports the Church and indeed the world through his life of prayer and solitude. He is assured of the prayers of his brothers and indeed of the whole Church. This kind of solitude is something we’re all called to in the Christian life. This physical solitude is a physical separation. However, in this physical separation, we’re able to enter into spiritual richness. Many of the great spiritual masters speak of purity of heart through an emptying of the self. In our deprivation, by God’s grace, we purify our self-will and physical pleasures.

Someone asked a venerable monk what the use of his life was and the vocation of the contemplative life in general. You seem to sit behind walls bringing no practical contribution to society. The monk answered, do you see how dark and scary the world can be? The person answered, yes. The monk answered, Well, just imagine how much worse the world would be without the prayers of those called to the contemplative life.

The man who has found solitude is empty, as if he had been emptied by death (New Seeds, 81).

Both physical and spiritual solitude is a way to the mystical country, the region of the heart. These forms of aloneness are tools for the pilgrimage towards the heart. An aid on our way to true union with God in the depths of our hearts. Solitude is not loneliness, although it can start out this way. It’s a way, again for us to find the One we’re truly seeking. The One who can fulfill and satisfy our deepest longings. Monks show us how to live in solitude by a departure from the world and consecrating their lives to this divine destination. This divine destination is not fully realized in the monastery but of course in heaven. But the monks are called to this physical separation and interior solitude in particular way. But, again, all of us living the Christian life are called to some form of solitude and learning to be alone.

The fuga mundi, that is flight from the world, from family and career, is not a running away but a running towards something greater than ourselves. As romantic and mysterious as it may sound, it has it’s challenges to live in a monastery under a monastic Rule and Abbot as do all other vocations in the Church. All of us Christians are called to some degree of this flight from the world. We do this by our state of mind in living in the world, witnessing to the Gospel in our daily lives, by choosing to live a more simple way of life in the world. Monks live in their cells in the monastery. In the world we’re called to live in the cell of our hearts. But we also should find a place where we can physically separate ourselves to be with our heavenly Father. A place where no one can see us, in obscurity, to hear His voice and labor with Him. In this physical place of solitude, we by God’s grace, develop an interior solitude. This learning to be alone is not done in vain but supports and strengthens us in work and daily activities.

There should at least be a room, or some corner where no one will find you or disturb you or notice you. You should be able to untether yourself from the world and set yourself free, loosing all the fine strings and strands of tension that bind you, by sight, by sound, by thought to the presence of other men (New Seeds, 81).

It has been the tradition of the English Benedictine Congregation to spend a half hour each day in meditation as part of our spiritual observance. Many of the monks make their meditation before the early morning Office of Vigils. This early part of the day is ideal for this type of prayer of quiet when the sun is still resting, the world still fresh. You can find monks scattered throughout the monastery. Some choose the chapel where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved, you may find some in the cloister garden, in one of the small parlors in front of the monastery, in their cells, on the back porch nestling a hot cup of coffee, or down in the woods behind the monastery. These are the places they’ve made to be alone with God in a deep and profound way. They are out of sight and mind even within the walls of a monastery but always held in the heart of the Father.

So, be encouraged to embrace this desire to be alone with our Heavenly Father. As we approach the holy season of Lent you may wish to begin to learn to be alone with God. Perhaps you may find a place in your home to develop a prayer corner or make time to visit your church for ten minutes of private prayer each day. You may wish to turn off your device for a period of time each day. In this place of your heart and in your home allow the Lord to lead you to the divine destination. The place where you’re fed with Divine Life and sustained in His love. The place where you can learn to be alone with Him in this life and to be with Him in the true Life to come.

It is here that you discover act without motion, labor that is profound repose, vision in obscurity, and, beyond all desire, a fulfillment whose limits extend to infinity (New Seeds, 81).

Pax,

Photo of Merton’s Hermitage, Dianne Aprile, The Abbey of Gethsemane: Place of Peace and Paradox, 150 Years in the Life of America’s Oldest Trappist Monastery

Fr. Aidan is a Benedictine monk and priest of the Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Louis in Saint Louis, Missouri. Father Aidan grew up in Saint Louis with his mother and father and two sisters in a working class Irish Catholic family. He was ordained to the priesthood in 2015, on the Feast of the Holy Name of Mary, and currently serves as the Pastor of Saint Anselm Parish in the Archdiocese of Saint Louis. Fr. Aidan holds a BA in English Literature from Webster University in Saint Louis, and a MDiv from Saint John XXIII National Seminary in Massachusetts.

Father Aidan prays his contributions will help the faithful discover how the Benedictine virtues of obedience and humility, can be helpful in their particular vocation to seek the image of Christ through purity of heart in their lives.

Father Aidan, thank you for sharing this with us. In today’s world one must intentionally seek out some solitude or it’s not likely to find you. Coincidently I am reading “Seven Storey Mountain” so may run across more on this.

Mr. Crescio,

So true about the solitude! Wonderful to hear you’re reading “Seven Storey Mountain.” Hope you’re enjoying it. You’ll have to offer a review. Thank you for reading. God bless,

Thanks for the reflection Fr. Aidan. This would seem to be an important part of the antidote to the noise spoken of by C. S. Lewis in the Screwtape Letters so lethally used by the enemy to distract us from what our heart truly desires, unity with God. It also makes me wonder if the ancient tradition of the Sabbath shouldn’t be taken more seriously by us today. If we shouldn’t intentionally try to make our Sabbath’s less noise-filled by intentionally unplugging for the day.

Father Aiden-

My compliments for a fine contemplative

exegesis of Seeds of Contemplation and its

authentic exemplars.

Father Aiden,

I am a former literature teacher and practicing poet and devotee

of poet Robert Lax, Columbia classmate of Brother

Louis, Thomas Merton. Both men shared

anem caram and as poet more original than Thomas..

A primer for Robert Lax is S.T. Georgiou’s

In the Beginning Was Love.

a copy (Better World Books) available.

Hello Mr. Belongie, Thank you for the recommendation of the Robert Lax. Maybe we can correspond via email if you wish about literature and things. God bless you.

Thank you for the recommendation of the Robert Lax. Maybe we can correspond via email if you wish about literature and things. God bless you.

Thank you for your kind thoughts. I was an English major in college. I’m a lover of the short story form. But do enjoy a poem once in awhile.

Father, thank you for this beautiful reflection on the labor and fruitfulness of solitude.