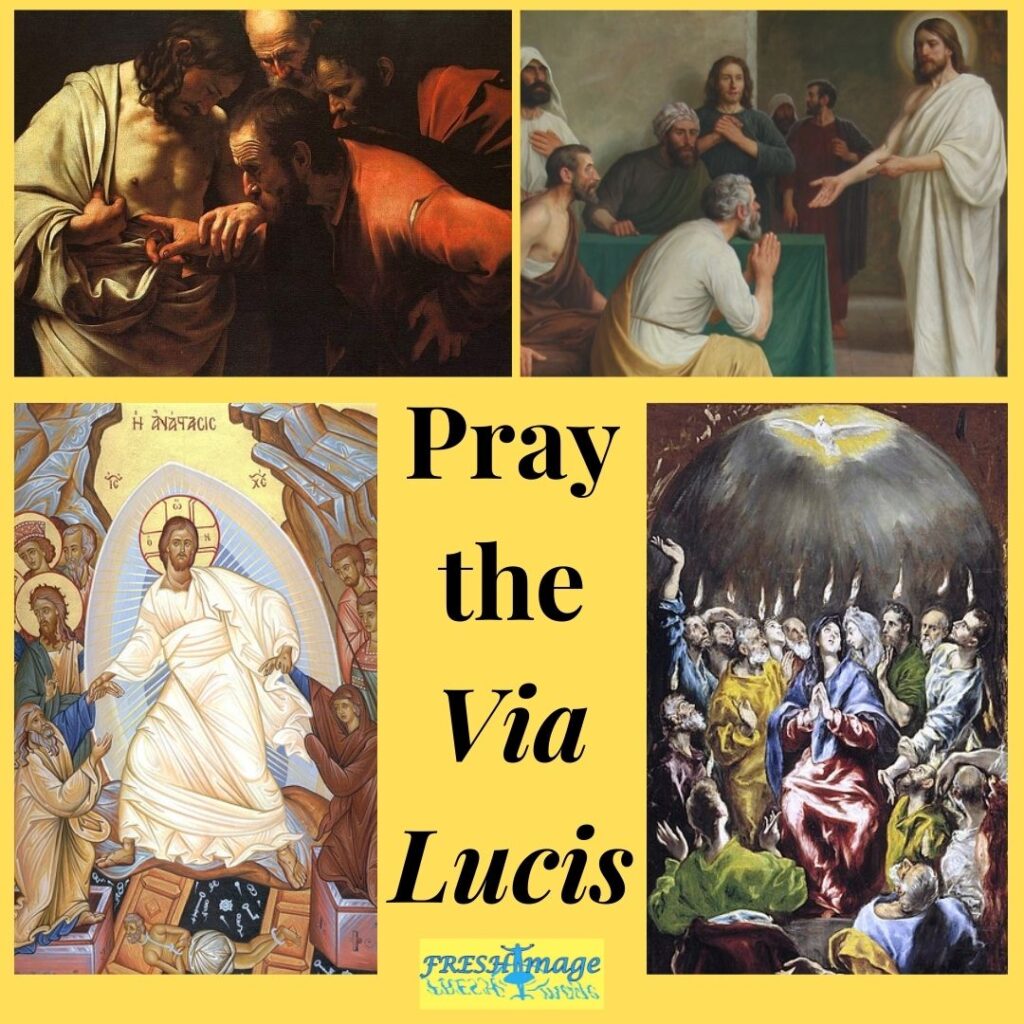

While not yet as popular as the Via Crucis (Way of the Cross), or, the Stations of the Cross, the Via Lucis (Way of Light), or, the Stations of the Resurrection, is a beautiful Easter compliment to it. As the Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy says, whereas the Via Crucis involves

the faithful in the first moment of the Easter event, namely the Passion, and helped to fix its most important aspects in their consciousness. Analogously, the Via Lucis, when celebrated in fidelity to the Gospel text, can effectively convey a living understanding to the faithful of the second moment of the Paschal event, namely the Lord’s Resurrection (153).

Focusing on the Resurrection, or, “the second moment of the Paschal event,” as the Directory puts it, is important for countless reasons. Here, we might suggest four.

First, as the Directory says, “through the Via Lucis, the faithful recall the central event of the faith-the resurrection of Christ…” (153). Put simply, this is it folks. If Jesus did rise from the dead, if we’re simply trading on pious fable here, we’re wasting our time. The whole of the Christian faith rests on the fact of the bodily Resurrection of Christ. What St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians in the first century AD holds just as true for us today as it did them: “if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have died in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied” (1 Cor. 15:17-19).

The Resurrection, to be sure, has not been without its naysayers. Preaching on the reality of the bodily Resurrection in the fifth century, St. Augustine highlighted the scars the Resurrected Christ bore on His body, keeping them, he says, “to heal the sound of doubt in our hearts.” Nevertheless, Augustine quickly adds, “on no other point is the Christian faith contradicted so passionately, so persistently, so strenuously, and obstinately, as on the resurrection of the flesh” (en. 2 Ps. 88.5). History bears out the truth in Augustine’s statement. From the very day it happened to the present, this central doctrine of Christianity has been disputed in various ways. For instance, the Gospel of Matthew makes clear that there was a rumor spread by some that the body had simply been stolen by the followers of Christ and that He did not, in fact, raise from the dead (See, e.g., Matt. 27:62-66 & 28:11-15). In our own time and place, people frequently claim that profession of faith in the bodily Resurrection of Christ is not necessary for a Christian, and prefer instead to understand it in other ways. For example, some will say that Christ merely rose in a spiritual way, the way the soul exists after bodily death, while others see in the Resurrection a metaphor for how God gets us through the toughest and darkest moments in our lives which ‘feel like death’ (See, e.g., Kimberley Winston, “Gospel Story of Jesus’ Resurrection a Source of Deep Rifts in Christian Religion”). The problem with this, of course, is that the Resurrection of Christ, and the Resurrection of the Body for all at the end of time (for some, as Jesus says, Resurrection to life and others to the resurrection of judgment, John 5:29), are central statements of the Creed. And if Christ has not been raised, as we have seen Paul say, then no one else will be either (1 Cor. 15:12-19). In the episodes we are asked to reflect upon as we move through these Stations of Light, it becomes clear that above all, they wish to impress the reality of the bodily Resurrection of Christ upon us.

But in what way, exactly, was the Resurrection of Christ bodily? Reflecting upon the passages of Scripture on the Via Lucis, it is apparent that, in some sense, the body Jesus rose in was similar to the one we possess now. We already saw Augustine highlight the scars Christ continued to bear on His body, a reality spotlighted by Jesus’ encounter with St. Thomas the Apostle in the 8th Station of the Way of Light. We also see Jesus eat with his disciples on the shores of the Sea of Tiberias in the 9th Station. Yet in the 4th Station it is clear that the disciples on the road to Emmaus don’t recognize Jesus initially, and the same can be said of Mary Magdalene in the 3rd Station, who mistakes Jesus for the gardener. Moreover, when Jesus appears to His disciples as a group for the first time as in the 6th Station, John tells us that “the doors of the house where the disciples met were locked…” (John 20:19). In short, the body Jesus arose in was like the ones we have now, yet different somehow.

This brings up the second important point of consideration, resurrection is not resuscitation. The Resurrection of Jesus is not simply His coming back to this life. If it were, it would hardly be worth making it the doctrine upon which all of Christianity hangs. For one, there are many people, including Jesus’ friend Lazarus (see John 11), who die bodily and are resuscitated, even more today with the help of modern technology like the defibrillator. Yet no one would base their entire lives, or, more to it, give their lives for these individuals because of it. Moreover, if the rising to life Jesus experienced were a mere resuscitation, he would die again. However, Paul says “that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him” (Romans 6:9). And, in the Book of Revelation, Christ tells John: “Do not be afraid; I am the first and the last, and the living one. I was dead, and see, I am alive forever and ever; and I have the keys of Death and of Hades” (Revelation 1:17-18). The message that the strangeness of Christ’s appearance and these passages from Scripture wish to impart on us is the fact that resurrection is precisely not resuscitation. It is not returning to this life from death, but a rising to life on the far side of death. Neither is it a denuding of the person, a stripping off of the body in Platonic fashion, but a being “further clothed,” as St. Paul says, the body elevated to a higher pitch of existence, completely transformed by being completely saturated with the life of God, what is mortal in us being “swallowed up by life” (2 Cor. 5:4; cf. 2 Cor. 5:2, 1 Cor. 15:52-57). What it means for a mortal body to be “swallowed up by life” or for it to “put on imperishability” and “immortality” is impossible to say with precision (1 Cor. 15:53-54), for it falls into the category of “what no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the human heart conceived” (1 Cor. 2:9).

While we may not be able to fully understand what this transformation of our bodies entails, we do know that one day we too will experience it, and until then, we must prepare for that everlasting day. How do we do this? By considering ourselves “dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus” (Roman 6:12). Or, as Augustine says, drawing from what is now the words exchanged in the “Preface Dialogue” of the Eucharistic Liturgy, it is to make the whole of our lives a sursum cor, ‘a lifting up of our heart to God’ (Sermon 229.3). How do we do this? Augustine answers:

Hoping in God, not in yourself; you, after all, are down below, God is up above; if you put your hope in yourself, your heart is down below, it isn’t up above. That’s why, when you hear Lift up your heart from the high priest, you answer, We have it lifted up to the Lord. Try very hard to make your answer a true one, because you are making it in the course of the activity of God; let it be just as you say; don’t let the tongue declare it, while the conscience denies it”(Sermon 229.3).

This is the third reason praying the Via Lucis is important, it instills in us an eschatological desire, if you will. By setting before us the episodes which took place between the Christ’s Resurrection and Ascension, it sets our gaze upon the horizon of eternity, asking us to look up and ahead, keeping our focus on where it is we hope to be some day so that we might not get bogged down in the struggles we face day to day in this valley of tears.

Nevertheless, this eschatological desire must follow the same trajectory of Christ if it is to be a true expression of the Divine desire, the divine love. And there is no way to make progress in our journey toward eternal happiness except to engage in the fullness of life this side of eternity. Said differently, the only way up, is, well, down. It is to put on the mind of Christ, as St. Paul says in Philippians (2:5) by imitating His humble self-sacrificing love which knew of no other way to love than to the very end (Philippians 2:6-8; cf. John 13:1). In short, if you want to lift up your heart to the Lord, give it away to your neighbor. For, as Our Lord said to St. Catherine of Siena:

all virtues are built on charity for your neighbors…Therefore as soon as the soul has conceived through loving affection, she gives birth for her neighbor’s sake. And just as she loves me in truth, so also she serves her neighbors in love (St. Catherine of Siena, The Dialogue, 7).

This final point of importance to consider is firmly impressed upon us by the praying of the Via Lucis. The final two Stations recount the praying of Mary and the Apostles for the Holy Spirit in the Upper Room, and then finally the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. The message is clear, with the gift of God’s Love poured out into our hearts (see Romans 5:5), we are not sent out of the world, but into it, as we pray in the 11th Station, sent to be the hands and feet of Christ in the world, of living as His Body, the Church, the sacrament of God’s presence and salvation in the world (Lumen Gentium, 1 & 9). By so forming us, the Directory writes, “the Via Lucis is a potential stimulus for the restoration of a ‘culture of life’ which is open to the hope and certitude offered by faith, in a society often characterized by a ‘culture of death’, despair and nihilism” (Directory, 153). This is a message the world, and especially the youth of today need to hear. While many seek to impress upon them that life really has no meaning, that it matters not what you do for it will all end in death anyhow so they may as well do as they please, the life of the Church stands athwart. The Christian life fully lived is an embodied reminder to the world that the way we live here and now matters eternally, and that death is neither to be sought nor feared, for in Christ it has no sting, and in Him its once menacing horizon has been transformed into the gates of eternal happiness (see 1 Cor. 15:55).

Your servant in Christ,

Tony Crescio is the founder of FRESHImage Ministries. He holds an MTS from the University of Notre Dame and is currently a PhD candidate in Christian Theology at Saint Louis University. His research focuses on the intersection between moral and sacramental theology. His dissertation is entitled, Presencing the Divine: Augustine, the Eucharist and the Ethics of Exemplarity.

Tony’s academic publications can be found here.