November 21

Today the Church celebrates the Memorial of the Presentation of Mary. This celebration has traditionally been kept with greater solemnity by our brothers and sisters in the Orthodox Church. Yet it remains on the Liturgical Calendar in the West. The reason for this is, as St. Paul VI taught, that “apart from their apocryphal content, [they] present lofty and exemplary values and carry on venerable traditions having their origin especially in the East” (Marialis Cultus, 8). The mention of apocryphal content in this quote from Paul VI is a reference to non-canonical writings from which celebrations like today’s have derived. In the case of today’s memorial, the narrative basis comes from a work which scholarly consensus dates to the 2nd century known as the Protoevangelium of James. Given that this memorial is so rooted in a non-canonical work, it is not difficult to find blogs around the web that refer to today’s memorial as “celebrating something that never happened,” and subsequently go on to focus their thoughts on the other half of the description given to today’s memorial in the Liturgy of the Hours, i.e., the dedication of a church built in honor of Mary the Mother of God near Jerusalem on November 21st in 543 AD.

Realizing that today’s overly scientific mentality lends itself to dismissing the unhistorical in favor of the verifiably historical, to suggest that we must choose one of these over the other is a simple false dichotomy. Regardless of its non-canonical and ahistorical roots, the account of the presentation of Mary found in the Protoevangelium of James is not only beautiful, but, to echo Paul VI, does indeed “present lofty and exemplary values” which, I would add, allegorically depicts the archetypal behavior of the Church as the Body of Christ, activity taking its basis from the liturgy celebrated in every church building and meant to spill out of its doors and into the world. Seen in this way, the two halves of today’s memorial are mutually implicative, and illuminating.

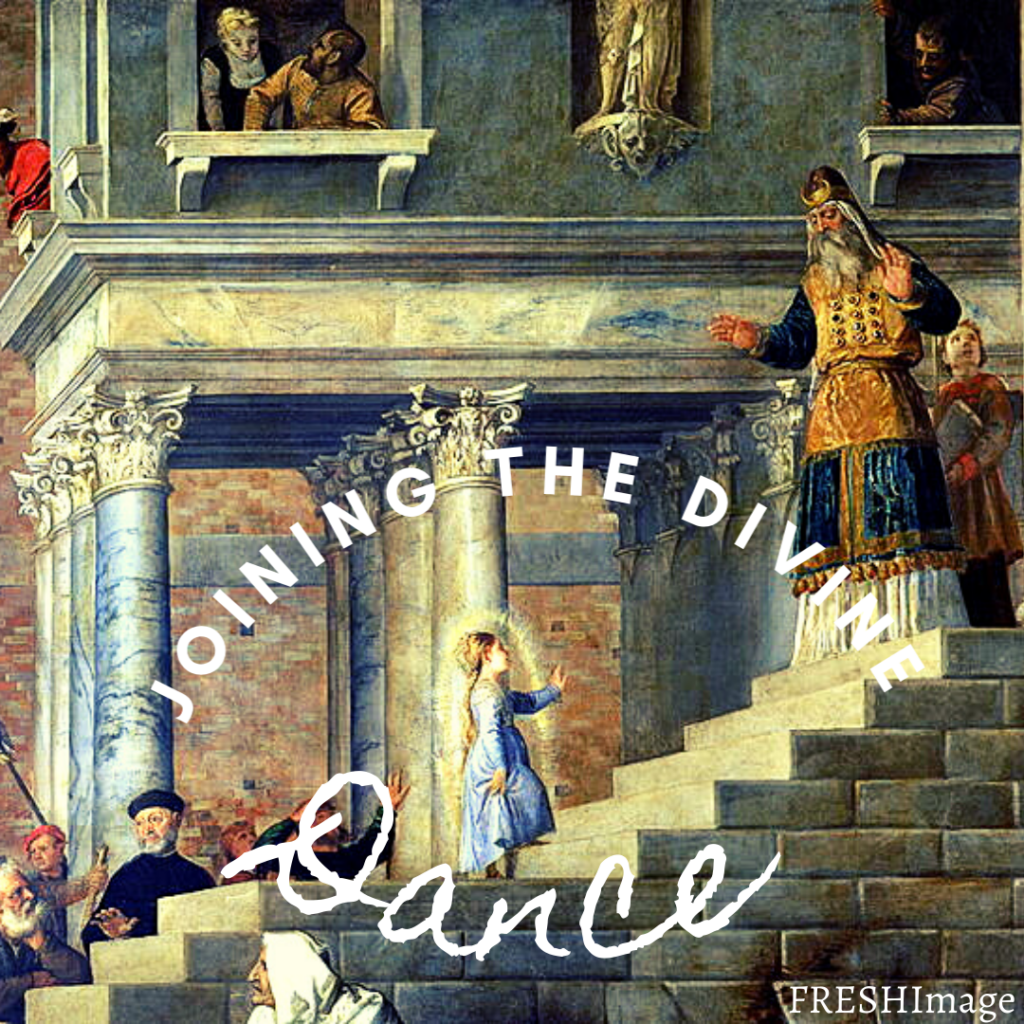

In addition to the scene depicting today’s memorial, the Protoevangelium of James in its totality seeks to present Mary the Mother of God as one who is favored and chosen by God from before her birth and full of God’s grace and completely dedicated to God throughout her life. It recounts how the childless Sts. Joachim and Anna promised to dedicate a child to God if they were blessed with one. By God’s grace they were, and when Mary was three years old they brought her to the Temple where “the priest welcomed her, kissed her, and blessed her: ‘The Lord God has exalted your name among all generations. In you the Lord will disclose his redemption to the people of Israel during the last days.” With that the priest set her on the third step of the altar, “and the Lord showered favor on her. And she danced, and the whole house of Israel loved her” (Protoevangelium of James, 7.7-10, my emphasis). Notice please the repeated emphasis on the number three in this account. Mary is presented at the Temple when she is three years old, and then she is placed on the third step of the altar and it is there, in the temple of God before the altar that she bursts forth in joyful dance.

This image of Mary’s uncontainable joyful youth, as all reverenced stories of the life of Our Lady, has something of the most profound nature to tell us. Mary is here held out to us as a mirror in which to gaze, and what we see in our gazing is both the reflection of the life of God most profoundly united to her and an image of the perfection to which we are called and must aspire as baptized children of God. The image of Mary dancing is indicative of the activity of the divine life of grace within her, and thus it simultaneously reveals something to us of the divine life itself by way of analogy, and of the appropriate human response to graced participation in that divine life. Addressing the latter first will shed light on the former, and there are two scriptural stories which the author of the Protoevangelium likely took inspiration from and are readily related to this beautiful image of Our Lady’s joy.

The first is that of John the Baptist leaping for joy in Elizabeth’s womb at the sound of Mary’s voice (Lk 1:41). In this scene it is Elizabeth who, the Scripture tells us, “filled with the Holy Spirit,” relates to us that it was in response to Mary’s greeting that the child in her womb leapt for joy (Lk 1:41 & 44). Thus, the same Spirit who overshadowed Mary so that she might conceive Our Lord (Lk 1:35) now animates both Elizabeth and John the Baptist in her womb. The spontaneous joy depicted in this scene mirrors that of Our Lady. In the child Mary’s case, she leaps, dances for joy at the presence of God in the Temple, and now as the very Temple of God Incarnate is joyfully danced before by the unborn child John. The second scriptural story that the author of the Protoevangelium could have been inspired by is found in the Old Testament Second Book of Samuel. In 2 Samuel 6:5, we are told that as the Ark of the Lord was brought into Jerusalem, “David and all the house of Israel were dancing before the Lord with all their might, with songs and lyres and harps and tambourines and castanets and cymbals.” There are several details to notice here. The first is simply all of the parallel lines that are accumulating as we explore this memorial, for David here dances before the Ark, i.e., before the very presence of God. Thus, there can be little doubt that when Luke recounts the scene of John the Baptist leaping in Elizabeth’s womb that he not only wanted to communicate the divinely inspired recognition of Christ by the child, but to portray Mary as the full realization of which the Ark in the Old Testament prefigured, i.e., that which contains within it the very presence of God.

The second detail to note has to do with David and gets us to what all of this human dancing has to tell us about the life of God. David is often seen by patristic thinkers, like Augustine, as a foreshadowing figure of Christ (e.g., Exposition 1 of Psalm 33.4). Second, the verb translated here as “dancing” is rooted in the Hebrew word sachaq, which is the same root of the word used to describe the activity of Wisdom in the presence of God at creation in Proverbs 8:30-31: “then I was beside him, like a master worker; and I was daily his delight, rejoicing (mə·śa·ḥe·qeṯ) before him always, rejoicing (mə·śa·ḥe·qeṯ) in his inhabited world and delighting in the human race.” Over the course of time, Church thinkers began to speak of the relationship of the Trinitarian Persons in a similar way, applying the word perichoreō (from peri-. ‘around,’ and choreō, ‘to sing and dance’). The thinker who gets most credit for this is St. John of Damascus, who described the relationship of the Trinitarian Persons as “without interval between them and inseparable and their mutual indwelling (perichoresin) is without confusion” (An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, 1.14.11). St. John of Damascus is here developing the use of a term that was first developed by St. Gregory of Nyssa and St. Maximus the Confessor after him to describe the mutual indwelling of divine and human that takes place as the result of the ongoing process of salvation begun at baptism. St. Maximus describes the salvation that begins with the gift of faith as “the inexpressible interpenetration (perichoresis) of the believer toward the object of belief…Enjoyment of this kind entails participation in supernatural divine realities. This participation consists in the participant becoming like that in which he participates” and it is this participation that “constitutes the deification of the saints” (Quaestiones Ad Thalassium, 59).

In her study on Eastern Liturgy, especially as took place at the Hagia Sophia, art historian Bissera V. Pentcheva describes how everything from the architecture of the great church to the movements of the liturgy, both the liturgy of the Word and the Eucharist, expressed the mirroring integration of the baptized into the very life of God. These liturgical movements were thought of in terms of perichoresis. In the liturgy various layers of activity unite and interpenetrate, the divine perichoresis is thought to be participated and mirrored by the angelic hosts who in turn are mirrored by the human participants in the liturgy who are drawn up into the divine life in the process, tuning their own movements to the eternal dance of divine love (Pentcheva, Hagia Sophia, 24). Lest we think that this sort of theological thought is limited to the East, we find St. Augustine articulating a similar liturgical theology in his exposition on the Psalms. In his exposition of Psalm 30, Augustine describes how the Totus Christus, the Whole Christ Head and Body, share one voice that is heard especially in the Psalms, saying, “he who did not disdain to take us up into himself, did not disdain either to transfigure himself, and to speak in our words, so that we in our turn might speak in his” (Exposition 2 of Psalm 30.3). Thus, in a way similar to the dynamics of the liturgy described by Pentcheva, for Augustine, we exercise and experience the salvation won for us by Christ existentially when we speak in unison with the one voice of the Totus Christus.

At this point we can connect the dots moving backwards and see how the dance of Our Lady is both a mirroring of the eternal divine dance of her Son, which she has been drawn up into precisely because of her perfect integration into the divine life. As children of so great a Mother, we who participate in the liturgy, most especially the Eucharistic Liturgy, are meant to mirror her mirroring divine dance. Yet our joining in the divine dance, while taking its rhythm from the liturgy, is not limited to the confines of the Church. Rather, it is meant to spill out into the streets of the world. Turning back to Maximus momentarily here is valuable. Just as Pentcheva described the faithful mirroring and participating in the divine perichoreō, Maximus associates this dynamic with the life of virtue to explain the existential process by which the human life is permeated by and interpenetrates the divine (Ambiguum 7.4). This finds echo in the same scriptural passage which spoke of the Personified divine Wisdom, the eternal Word’s dance before God at creation, for in that same chapter Wisdom is associated with the virtues of prudence (Proverbs 8:5 & 12) and justice (v. 20), and in the book by the same name, Wisdom is associated with all four traditional cardinal virtues (Wis. 8:7). Basing his thought on 1 Corinthians 1:24, Augustine too will throughout his career associate the life of virtue enabled by the Holy Spirit with participation in the life of Christ, the Son of God Incarnate (see, e.g., The Catholic Way of Life, 1.15.25-1.16.27).

Moreover, it is absolutely imperative for Augustine that the life we participate in, the divine dance which we are attuned to and trained in by the Divine Liturgy spill out of the doors of the church into the streets of the world. For it is precisely through the action of the faithful in their day to day lives that others are called to communion with the divine in accordance with the will of God (Exposition of Psalm 96.10). In other words, the exemplary lives of virtue lived day to day by individual Christians have a rhetorical force in society, calling others to conversion. Accordingly, Augustine describes Christians as living sermons (Teaching Christianity, 4.29,61), the light of the world (Exposition of Psalm 65.3), and speaks of the radiance of their virtue shining before others (Exposition of Psalm 71.5). More to it, he will speak of the life of virtue as a perpetual prayer or song (Exposition of Psalm 148.4), the alleluia’s danced throughout the world to the song of God’s commandments played to us by the Holy Spirit (Exposition of Psalm 128.1), Augustine referring to this song as being played on the ten-stringed lyre, one string for each commandment of the Decalogue (Sermon 33.1). We see then, that many of the same images used by Pentcheva are used by Augustine to speak of the everyday life of Christian virtue. Thus, it is imperative that the liturgical dance we experience within the walls of the church spill out into the streets of the world so that others might be persuaded to dance with us.

In a sermon written for today’s memorial, St. Gregory Palamas taught “by God Himself, the Mother of God was proclaimed and given to [Joachim and Anna] as a child, so that from such virtuous parents the all-virtuous child would be raised. So in this manner, chastity joined with prayer came to fruition by producing the Mother of virginity, giving birth in the flesh to Him Who was born of God the Father before the ages.” Today’s memorial calls us to remember the life of Our Lady, the living Ark and Temple of our Lord Jesus Christ, who allows Virtue Himself to completely animate her life, making of it one harmoniously beautiful divine dance. Today, she calls us to imitate her dance steps, her virtues. Thus, as we participate in the liturgy this weekend, it is appropriate to contemplate her virtues and ask God to grant us a share in these divine gifts. Perhaps we may focus on what St. Louis de Montfort called the “ten principle virtues of Mary”: humility, lively faith, continual prayer, mortification, purity, charity, patience, sweetness and wisdom (True Devotion to Mary, 108). In this way, through her intercession and the power of the Holy Spirit, we too might join in the divine dance and persuade others to join us.

Your servant in Christ,

Tony Crescio is the founder of FRESHImage Ministries. He holds an MTS from the University of Notre Dame and is currently a PhD candidate in Christian Theology at Saint Louis University. His research focuses on the intersection between moral and sacramental theology. His dissertation is entitled, Presencing the Divine: Augustine, the Eucharist and the Ethics of Exemplarity.

Tony’s academic publications can be found here.

Thanks. It helps illuminate my understanding the life of Mother Mary.

Really enjoyed rereading this. Very well put together.

Beautiful reflection of Our Blessed Mother! May we all “dance” as she does with her help and intercession!

Well done , Tony. Excellent work!

Thanks very much!